CHAPTER:1

Avian Evolution And Diversity

LEARNING OUTCOMES

- Describe the evolutionary history of birds

- Discuss the diversity of birds

Evolutionary History of Birds

The evolutionary history of birds is still somewhat unclear. Due to the fragility of bird bones, they do not fossilize as well as other vertebrates. Birds are diapsids, meaning they have two fenestrations or openings in their skulls.

Birds belong to a group of diapsids called the archosaurs, which also includes crocodiles and dinosaurs. It is commonly accepted that birds evolved from dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs (including birds) are further subdivided into two groups, the Saurischia (“lizard like”) and the Ornithischia (“bird like”). Despite the names of these groups, it was not the bird-like dinosaurs that gave rise to modern birds. Rather, Saurischia diverged into two groups: One included the long-necked herbivorous dinosaurs, such as Apatosaurus. The second group, bipedal predators called theropods, includes birds. This course of evolution is suggested by similarities between theropod fossils and birds, specifically in the structure of the hip and wrist bones, as well as the presence of the wishbone, formed by the fusing of the clavicles.

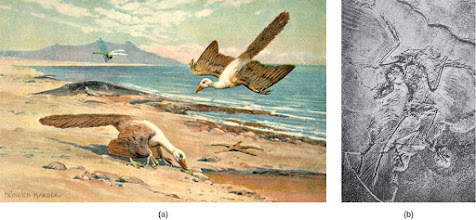

One important fossil of an animal intermediate to dinosaurs and birds is Archaeopteryx, which is from the Jurassic period.

Archaeopteryx is important in establishing the relationship between birds and dinosaurs, because it is an intermediate fossil, meaning it has characteristics of both dinosaurs and birds. Some scientists propose classifying it as a bird, but others prefer to classify it as a dinosaur. The fossilized skeleton of Archaeopteryx looks like that of a dinosaur, and it had teeth whereas birds do not, but it also had feathers modified for flight, a trait associated only with birds among modern animals. Fossils of older feathered dinosaurs exist, but the feathers do not have the characteristics of flight feathers.

(a) Archaeopteryx lived in the late Jurassic Period around 150 million years ago. It had teeth like a dinosaur.

(b) It had flight feathers like modern birds, which can be seen in this fossil.

It is still unclear exactly how flight evolved in birds. Two main theories exist, the arboreal (“tree”) hypothesis and the terrestrial (“land”) hypothesis.

The arboreal hypothesis posits that tree-dwelling precursors to modern birds jumped from branch to branch using their feathers for gliding before becoming fully capable of flapping flight. In contrast to this, the terrestrial hypothesis holds that running was the stimulus for flight, as wings could be used to improve running and then became used for flapping flight. Like the question of how flight evolved, the question of how endothermy evolved in birds still is unanswered. Feathers provide insulation, but this is only beneficial if body heat is being produced internally. Similarly, internal heat production is only viable if insulation is present to retain that heat. It has been suggested that one or the other—feathers or endothermy—evolved in response to some other selective pressure.

Diversity of Birds

During the Cretaceous period, a group known as the Enantiornithes was the dominant bird type. Enantiornithes means “opposite birds,” which refers to the fact that certain bones of the feet are joined differently than the way the bones are joined in modern birds. These birds formed an evolutionary line separate from modern birds, and they did not survive past the Cretaceous.

Shanweiniao cooperorum was a species of Enantiornithes that did not survive past the Cretaceous period.

Along with the Enantiornithes, Ornithurae birds (the evolutionary line that includes modern birds) were also present in the Cretaceous. After the extinction of Enantiornithes, modern birds became the dominant bird, with a large radiation occurring during the Cenozoic Era. Referred to as Neornithes (“new birds”), modern birds are now classified into two groups, the Paleognathae (“old jaw”) or ratites, a group of flightless birds including ostriches, emus, rheas, and kiwis, and the Neognathae (“new jaw”), which includes all other birds.

Bird diversity is much greater than that of reptiles, amphibians and mammals respectively. Presently, there are 10,711 extant species and 158 extinct species of birds of the world. The diversity is astounding, with birds existing almost everywhere in the world.

Birds live all over the world. They range in size from the two-inch bee hummingbird to the nine-foot ostrich. More than half of the known birds on earth are perching birds. As we just learned, birds first appeared during the Cretaceous, about 100 million years ago. Birds diversified dramatically round about the time of the Cretaceous–Palaeogene extinction event 66 million years ago, which killed off all the non-avian dinosaur lines. Birds, especially those in the southern continents, survived this event and then migrated to other parts of the world.

Modern birds have wings which are more or less developed depending on the species; the only known groups without wings are the extinct moa and elephant birds. Wings, which evolved from forelimbs, gave birds the ability to fly. Later many groups evolved with reduced wings, such as ratites, penguins, and many island species of birds. The digestive and respiratory systems of birds are also adapted for flight. Some bird species in aquatic environments, particularly seabirds and some waterbirds, have evolved as good swimmers.

Some birds, especially crows and parrots, are among the most intelligent animals. Several bird species make and use tools. Many social species pass on knowledge across generations, a form of culture. Many species annually migrate great distances. Birds are social. They communicate with visual signals, calls, and bird songs. They have social behaviours such as cooperative breeding and hunting, flocking, and mobbing of predators.

Most bird species are socially monogamous, usually for one breeding season at a time, sometimes for years, but rarely for life. Other species are polygynous (one male with many females) or, rarely, polyandrous (one female with many males). Birds produce offspring by laying eggs which are fertilised by sexual reproduction. They are often laid in a nest and incubated by the parents. Most birds have an extended period of parental care after hatching. Some birds, such as hens, lay eggs even when not fertilised, though unfertilised eggs do not produce offspring.

Do Birds Mate for Life?

We’ve all heard it countless times: Certain species of birds mate for life, including geese, swans, cranes, and eagles. It’s a true statement, for the most part, but it’s only part of the story. Lots of monogamous bird species cheat, and some “divorce”—but at rates much lower than humans.

About 90 percent of bird species are monogamous, which means a male and a female form a pair bond. But monogamy isn’t the same as mating for life. A pair bond may last for just one nesting, such as with house wrens; one breeding season, common with most songbird species; several seasons, or life.

Social monogamy seems to be more common than sexual monogamy. Social monogamy refers to the male bird’s role in parenting. In most songbird species, the male defends a nest and territory, feeds his incubating mate, brings food to nestlings and feeds young fledglings. In some species, especially when the male and female look alike, the male will even incubate eggs. Social monogamy is when a male bird is actively involved in nesting and rearing the young.

But genetic testing of songbird nestlings, even in socially monogamous species, shows that the father who sired them isn’t necessarily the one who is helping to rear them. In other words, a socially monogamous female songbird sometimes “cheats” on the male with whom she has a bond. And her socially monogamous mate may have fathered eggs in other nests.

Sometimes a female bird carrying an egg fathered by her bonded mate, will lay that egg in a different nest of the same species. So when you happen upon a songbird nest full of eggs — even of a socially monogamous species — you can’t be sure who is the biologic father — or mother — of those eggs.

In other words, socially monogamous birds are not necessarily faithful partners, but they care for each other and for the young of their nest. Rearing young together does not imply sexual fidelity. Studies of eastern bluebirds have found that nests with mixed parentage — that is, they have eggs by more than one father, or more than one mother, or both — are not uncommon.

Between one in 10 and one in three eggs in a female cardinal‘s nest has genes that don’t match her partner, and less commonly, they don’t even match her own. But because of that pair bond to rear the young, they are considered socially monogamous.

According to The Birder’s Handbook, “It is perhaps best simply to consider monogamy as a social pattern in which one male and one female associate during the breeding season, and not to make too many assumptions about fidelity or parentage.”

The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior says that 90 percent of all bird species are socially monogamous, but some level of cheating is common. Cheating, or “extra-pair copulation” also occurs, but rarely, among birds of sexually monogamous, mated-for-life species, “but is not yet known how many species engage in extra-pair copulations, since many species remain to be studied. However, it appears that genetic monogamy may be the exception rather than the rule among birds.”

BIRDS AT RISK

Birds are a beautifully diverse class of animal; however, many species are at risk. As of 2009, 1,223 species of birds were marked as endangered by IUCN’s 2009 Red List. In the United States alone, about 74species of birds were at risk.

0 Comments